Robert Edwards is a widely celebrated British physiologist and embryologist. He gained fame for his groundbreaking work in reproductive medicine, specifically in vitro fertilization (IVF). His pioneering efforts led to the first successful IVF conception, resulting in the birth of Louise Brown, the world’s first “test-tube baby.” Read more at imanchester.info.

Early Years of the Renowned Embryologist

Robert Edwards was born in 1925 in Batley, West Yorkshire. While little is known about his early interests, his scientific journey began in Manchester, where he moved as a young man.

He attended Central Secondary School in Manchester before serving in the army. Growing up in the post-war era, Edwards developed a fascination with biology and human development. Following his military service, he pursued a biology degree at Bangor University and later studied at the Institute of Animal Genetics and Embryology at the University of Edinburgh, where he earned his Ph.D.

After completing his education, Edwards embarked on a long academic career. He worked as a research fellow at the California Institute of Technology and with the scientific team at the National Institute for Medical Research in Mill Hill. Never one to stop learning, he also studied at the University of Glasgow and Cambridge University, where he worked as a Ford Foundation research fellow in the Department of Physiology and became a fellow at Churchill College, Cambridge.

Work on Human Fertilization

Edwards’ interest in reproductive biology emerged during his time in Edinburgh. He was particularly intrigued by the possibility of fertilizing human eggs outside the body—a revolutionary concept at the time. The mid-20th century was a period of significant scientific advancements, but infertility remained a pressing issue for many couples. Edwards devoted his life to developing medical interventions to overcome this barrier.

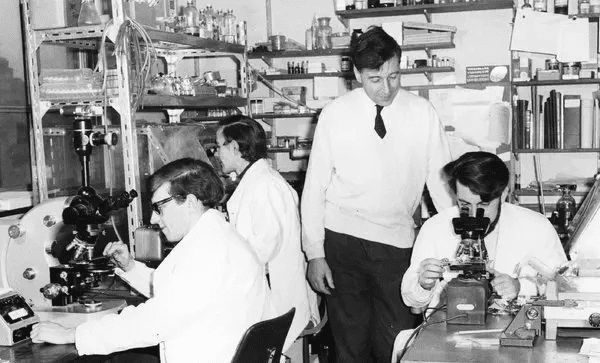

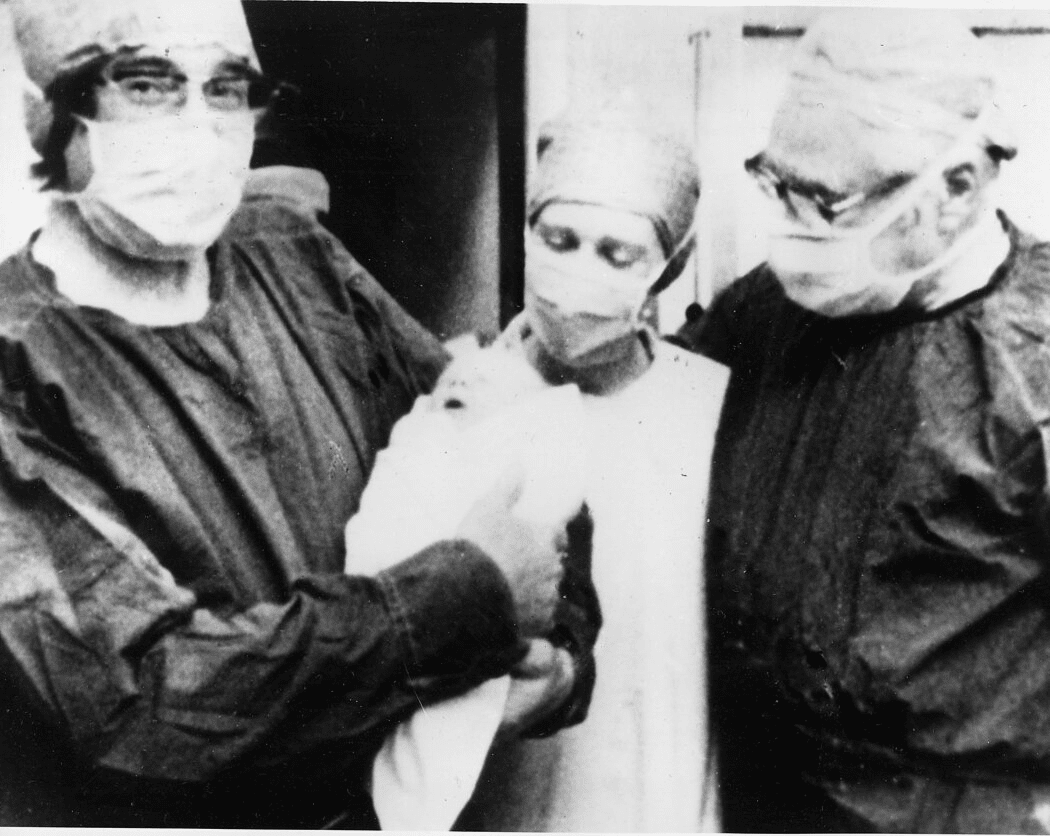

In the 1960s, Edwards began collaborating with gynecologist Patrick Steptoe, an expert in laparoscopy. Together, they pursued a procedure that would allow human eggs to be fertilized in a laboratory and then implanted in a woman’s uterus.

Despite their noble intentions of helping couples achieve parenthood, their research faced significant skepticism and ethical opposition. Both the public and the Medical Research Council, which refused to fund their studies, expressed serious concerns. Undeterred, Edwards and Steptoe pressed on with their work on artificial fertilization.

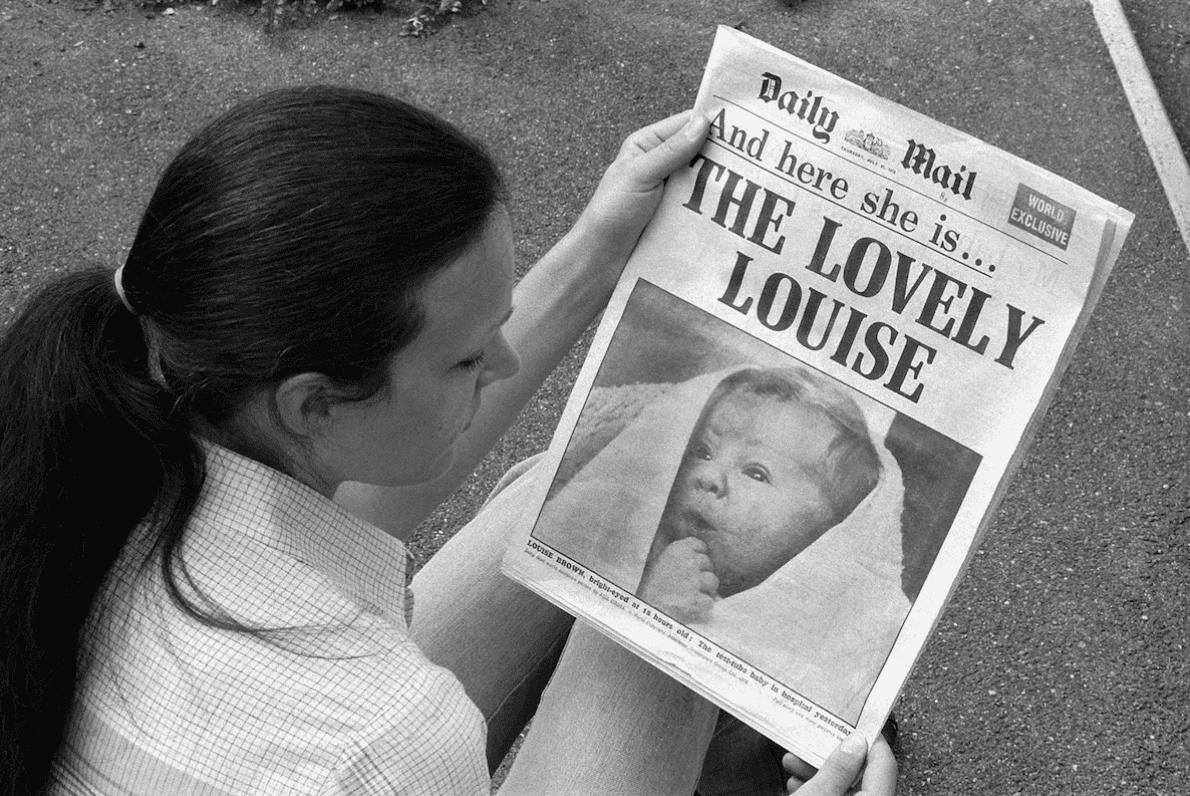

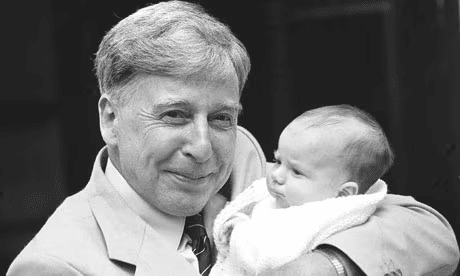

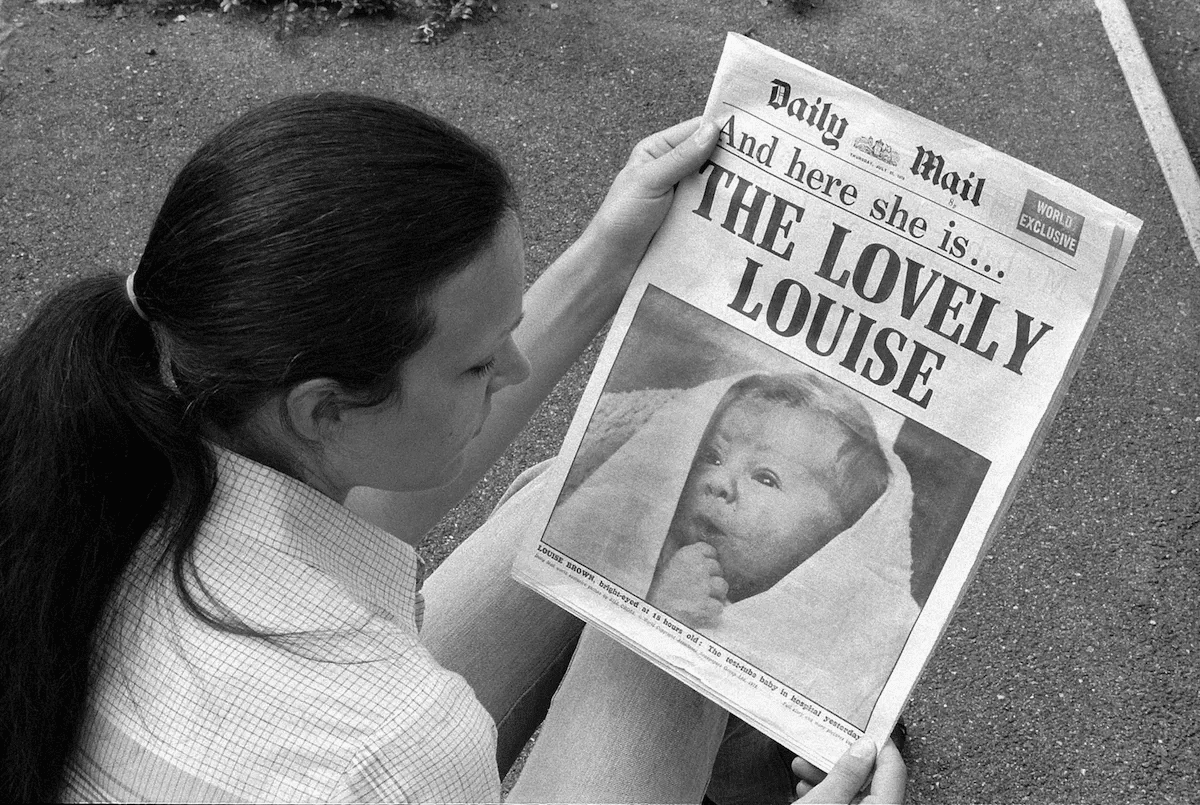

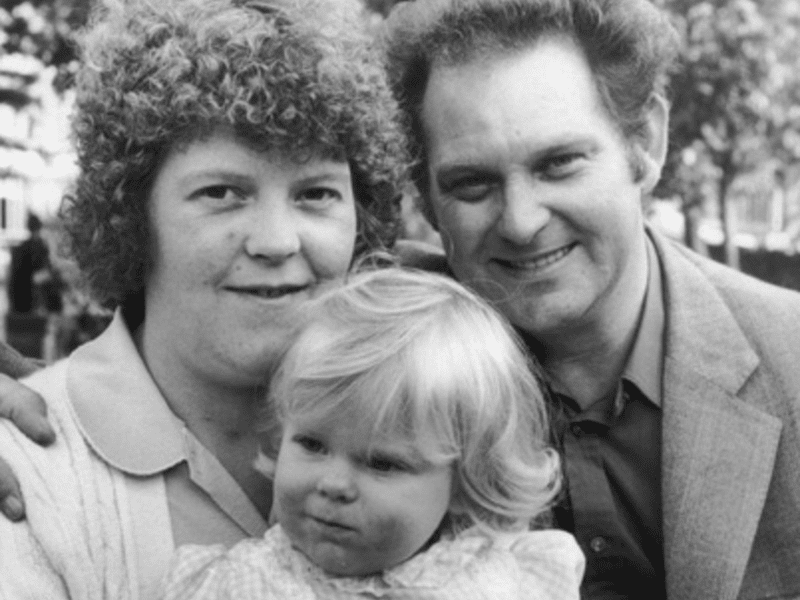

Edwards developed specialized human culture media that facilitated the fertilization and early cultivation of embryos. Meanwhile, Steptoe employed laparoscopy to retrieve eggs from patients with tubal infertility. Their collaboration culminated in the birth of Louise Brown in 1978, the world’s first “test-tube baby.” This monumental achievement marked a new era in reproductive medicine and became a symbol of hope for millions of couples struggling with infertility.

How Edwards’ Discovery Changed the Lives of Women Worldwide

The development of IVF revolutionized the lives of women and couples facing infertility. Before IVF, women unable to conceive naturally had few options and often faced social stigma. Infertility significantly impacted women’s emotional well-being, leading to feelings of inadequacy, depression, and heightened anxiety. Edwards’ work transformed the lives of these women by giving them the chance to experience pregnancy and childbirth.

For women who once believed parenthood was unattainable, IVF provided a path to motherhood. This scientific breakthrough not only brought immense joy and fulfillment but also strengthened family bonds and enriched lives.

IVF Statistics and Life After the Discovery

Since the mid-20th century, Edwards’ IVF technology has undergone significant refinement. As of 2010, the method he developed had led to the births of approximately 4 million children, including around 170,000 conceived through donor eggs and embryos.

Their pioneering IVF method not only delivered on its initial promise but also paved the way for further innovations, such as intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI), preimplantation genetic diagnosis (PGD), and stem cell research.

IVF expanded opportunities for families. It enabled single women, same-sex couples, and individuals with genetic disorders to have biological children, thereby challenging traditional notions of family and broadening the scope of parenthood.

While IVF’s success rates and accessibility have improved dramatically in the 21st century, Edwards’ work laid the foundation for these advancements. Procedures like PGD now allow for the screening of embryos for genetic disorders, enhancing the likelihood of a healthy pregnancy—a direct result of Edwards’ revolutionary contributions.

Challenges and Ethical Debates

Edwards and Steptoe’s journey to establish IVF was not without its challenges. Their groundbreaking work faced ethical scrutiny, religious opposition, and skepticism from the scientific community. Critics questioned the morality of creating life in a laboratory and raised concerns about potential health risks for IVF-born children.

However, Edwards addressed these issues through rigorous scientific research, advocating for ethical practices in reproductive medicine. His efforts set a precedent for responsible IVF and related technologies, ensuring the well-being of both parents and children.

Following their initial success, Edwards and Steptoe founded Bourn Hall Clinic, where they continued to refine IVF techniques and train new specialists.

A Legacy of Hope

Edwards’ contributions to reproductive medicine have left an indelible mark on the world. His work earned him numerous accolades, including the 2010 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. However, his greatest legacy lies in the millions of families who have experienced the joy of parenthood thanks to IVF. Edwards’ groundbreaking research continues to inspire hope and transform lives worldwide.